Sometimes instead of creating a logger and then passing it around, it is convenient to just use a

global logger.

The standard log library allows you to both create a custom logger using

log.New() or directly use a standard logger instance by calling

the package helper functions log.Printf() and the like.

zap provides such a functionality as well using zap.L() and zap.S(), however using them

didn’t seem so straight forward to me.

The various implementations of field encoders provided in zap can sometimes feel inadequate. For

example, you might want the logging output to be similar to that in syslog or other common log

formats. You might want the timestamps in the log to ignore seconds, or the log level to be wrapped

within square brackets.

To have your own custom formatters for the metadata fields you need to write custom encoders.

Using the logger presets in zap can be a huge time saver, but if you really need to tweak the

logger, you need to explore ways to create custom loggers. zap provides an easy way to create

custom loggers using a configuration struct. You can either create the logger configuration using a

JSON object (possibly kept in a file next to your other app config files), or you can statically

configure it using the native zap.Config struct, which we will explore here.

I was intrigued when Uber announced zap, a logging library for Go with claims of really high

speed and memory efficiency. I had tried structured

logging earlier using logrus, but while I did not experience

it myself, I was worried by a lot of folks telling me about its performance issues at high log

volumes. So when zap claimed performance exceeding the log package from standard library, I had

to try it. Also, its flexible framework left the door open to a future plan of mine of sending logs

filebeat style to ELK.

The documentation for the library was pretty standard, but I

could not find a reasonable introduction to explore the various ways one can use the library. So I

decided to document some of my experiments with the library.

I collected my code examples in Github, and decided to

break it up into a series of posts.

I admit I had not paid much attention to Netlify earlier. It sort of seemed like yet another web performance related startup.

But on reading Fatih’s article on hosting Hugo on Netlify, it piqued my interest. A CDN/hosting service which puts your content in caches all around the world, and triggers Hugo (and bunch of other common scripts) on Github commits? And all this for free? Sounds too good to be true, and memories of Posterous floated in my mind.

But again, the best part of using static blogging software like Hugo, is that there is so less to lose from trying out a new hosting option - no databases to setup, no old content to migrate.

And so i decided to try it out as well. And it turned out to be blindingly simple! Netlify turned out to be awesome!

Here are all the stuff I needed to do to move my Hugo hosting from my shared hosting account at Dreamhost to Netlify.

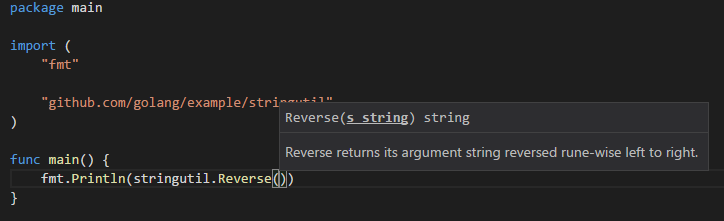

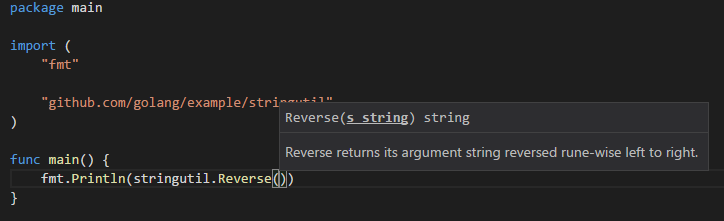

Soon after I reviewed GoLand, I discovered VS Code - a general purpose editor with

superlative support for Go. And I have been impressed enough to

stay.

As I understand Go more, some of the concepts tend to make my head hurt. Sometimes, innocent examples

in various tutorials hide such deep concepts, that it takes a while for me to decode it all.

Here is an example. In various tutorials, pauses are made using time.Sleep().

The first time I saw an example like the following, it made me stop in my tracks.

package main

import (

"time"

)

func main() {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

}

Seems like Jetbrains has finally ditched that weird name for their Go IDE and changed it to a

more palatable, but not really very inventive version (come on, I think PyCharm is a pretty nice

name for a Python editor).

Gogland is now GoLand!

I have been using Hugo as a static website generator for a while. I love the speed, coming from

its Go origins. I love a static website generator for the peace-of-mind it gives me (No did I forget to update my XXX

blog software after that bug came out? ).

But of course, it is not all peachy.

The sun is exactly overhead twice a year in Lahaina, Hawaii, once in May and

once in July. Poles don’t cast shadows, giving the urban landscape an eerie

appearance. Hawaii is the only state in the US where the sun’s rays are

perpendicular to the surface of Earth. It’s called a subsolar

point.

Via Boingboing

![[FSF Associate Member] [FSF Associate Member]](/images/fsf-371257.png)

![[PSF Supporting Member] [PSF Supporting Member]](/images/psf-supporting-member-badge-small.png)